Despair

‘The gifted architect will not be understood and this will cause him a thousand irksome setbacks’ – Etienne-Louis Boullée, Essai sur l'Art (1796)

Buildings are monuments to humanity. Symmetry, balance, contrast, and space must be reflected in the built environment. Clean lines merge with light to provoke some reaction in the viewer, something visceral should be felt when looking at a building. Modern architecture does not provoke and so the builder does not inspired by them. As I write, all I would like to build is probably illegal: imposing buildings that make liberal use of stonework and sculpture constructed with an emphasis on symmetry. Having spent time trying to reform planning laws, I co-founded a housing policy think tank in Ireland. I am now convinced legislative change is only part of the answer if architecture’s place in the engine of progress is to be regained. Part of this involves capturing the spirit of numerous neoclassical architects, chief among these is Etienne-Louis Boullée (1728 – 1799). His visions were so fantastic, few were built and though Boulléehas been largely forgotten, now is the time to rehabilitate him.

Working amidst the dying light of the Ancien Régime, Boullée was heavily influenced by advances in science, geometry and art that offered the possibility of successfully channelling the spirit of the cenotaphs and temples of Ancient Rome and Classical Greece, societies that were so defined by their public works. By taking the torch from Boullée and embracing his philosophy, to inspire man at a time in which great leaps in science and technology make abundance possible, this can be achieved, modern civilisation can build more. Civilisation needs more Boullées.

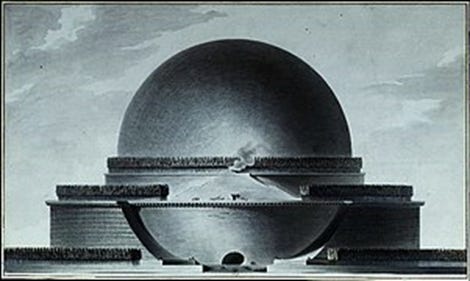

A key aspect of Boullée’s work is the idea of architecture parlante or speaking architecture, buildings must explain their own function; one way of achieving this is putting allegorical sculptures and designs at their core. Stretching architecture to its limits has a purpose beyond the visual, it gives a glimpse of the technologically possible. Newton’s Cenotaph, reminiscent of the Vegas Sphere, was pitched as a burial chamber for the physicist with the tomb to lie empty as a metaphor for the chasm left by Newton’s death. Indeed, the fact that the cenotaph is sacred and the sphere profane speaks to how some aspects of society have devolved.

Newton’s Cenotaph - elevation

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the same way as Boullée’s Newton’s Cenotaph was deemed too ambitious, too unwieldy and too flamboyant by his peers, my visions of monuments to progress would violate some aspect of Ireland’s Planning and Development Act (2000) or some aspect of New York City’s Building Code (1968) – legislation I have recently familiarised myself with. At 500 feet in diameter and taller than the Pyramids of Giza, Newton’s Cenotaph would violate Ireland’s restrictions on building height, normally no more than eight storeys for commercial use or three storeys for residential use with few apartment blocks exceeding five storeys. New York City’s Planning Commission would not tolerate the prospect of such a globe being built with many prominent architects including Le Corbusier decrying the city for this reason. Building is both art and science: the tension between the subjective and the objective creates the tension required for creativity.

The Cenotaph’s three-tiered cylindrical base creates the illusion of a buried volume made more convincing by the tiered ramps that ensconce the building. Such ramps are illegal in New York City: stairs must not be greater than 75 feet in height. The rows of cypress trees, symbols of endurance and mourning, would draw the ire of some Irish residents’ association, fearful of minute changes to the skyline and the perceived risk of declines in the value of their homes or that more strangers would set foot in ‘their’ area. Only recently have such groups been banned from taking cases against planning proposals directly to Ireland’s High Court though the tyranny of the vocal minority lives on in many aspects of Ireland’s planning process. The interior of the Cenotaph contains a long, low corridor, likely too low for Ireland’s current planning regime, that would guide people to the sphere's base. Symmetry is maintained by the building’s set piece, a square platform supporting an empty tomb for Newton, like the trees, the empty tomb embodies the vastness of the science Newton discovered.

The little light in the Cenotaph would be enhanced by an astrolabe at night, reminiscent of the roof box at Newgrange, a neolithic Irish tomb. Boullée’s astrolabe would imitate the sun and remind one of all that is possible, the juxtaposition between light or knowing and the mystery of the dark would imbue the onlooker with a greater appreciation for all that knowledge offers. Newgrange operates similarly during the summer and winter solstices. In the same way bursts of inspiration spark innovation in the hard sciences, for example, these structures become something more through their use of light. Too often, modern architecture’s application of light relies on creating exotic shapes that do not create a sense of awe, for which Bjarke Ingles’ all-glass Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet is an example.

Newton’s Cenotaph - dome at night

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Newgrange

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Newgrange’s Roof Box

Source: Shadows and Stone

Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet - exterior

Source: Archdaily

Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet - interior

Source: Audemars Piguet

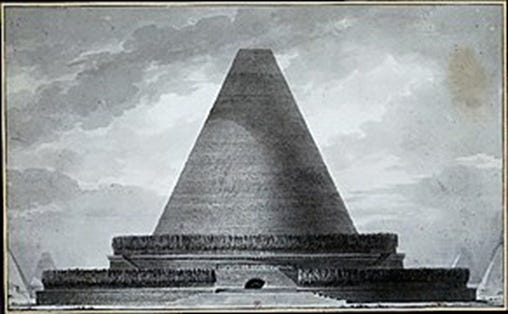

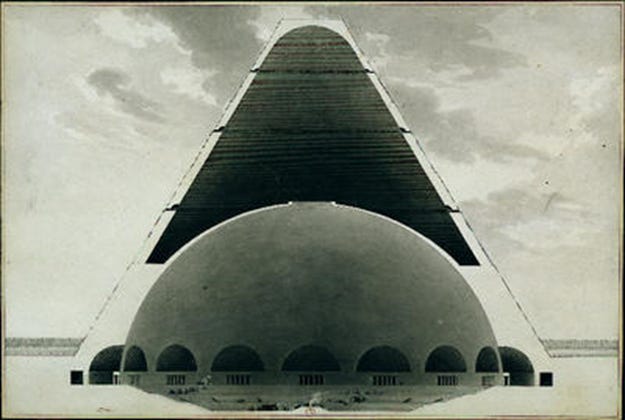

Modern architecture is dead with its unwillingness to challenge people’s emotions, there is a sameness in today’s monuments with their aversion to scale, today’s skyscrapers are indistinguishable, a fate aided by stale planning regulations that leave no room for the hope offered by the possible. Boullée’s Egyptian pyramid, lies uncapped, emphasising that death is not the end, uses its sheer scale as a public monument. The semi-circular entrance with its gently sloping stairs suggests that something is hidden, some mystery, a sense that modern architecture refrains from embracing. The symmetry of the pyramid lies in stark contrast to the modern buildings that have scarred so many streets. Irish planning regulations do not refer to the aesthetic aspects of architecture besides implementing guidelines that restrict creativity. Some regarding safety are critical, others decreeing height limits have surely contributed to the bungalow blight that stands as an affront to Ireland’s colourful history of ambitious building or the meekness with which public buildings have been built. Boullée’s pyramid is big, though not uncouth, unlike many of New York’s skyscrapers. Its use of stone gives it a gracefulness not evident in the panes of glass that sparkle in New York’s skyline.

Egyptian Pyramid - elevation

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Egyptian Pyramid – Interior

Source: BLDG Blog

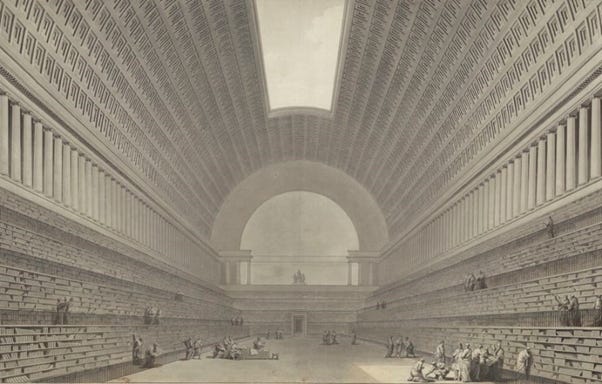

The ultimate monument to man is the public library. Boullée’s 1785 proposal for the French National Library, the Bibliotheque du Roi, proposes a space whose inherent purpose is to challenge. The set piece, a vaulted reading room adorned with statues of gods, consists of an open vaulted space with four tiers of bookshelves. Active discussion is encouraged through the central space designed for the intense discussion of knowledge. I am aware of no libraries today that allow for such unstructured conversation amongst books. The contrast between light and dark, the chiaroscuro, of Boullée’s planned library emphasises the completeness offered by the pursuit of knowledge.

Having originally dreamt of becoming a painter, Boullée’s vision has the essence of Raphael’s The School of Athens, where the library’s size, perspective and openness are critical to its identity and thus to the Aristotle and Plato of the painting. Buildings bind the tapestry of history, combining the rich architectural tastes of Ancient Greece with the nervous hope of pre-revolutionary France. In New York City, the Schwarzman Library has been open to the public for just over a century. Its high ceilings, Vermont marble and wood panels represent the pinnacle of the Beaux Arts style popular at the turn of the 20th century, uncoincidentally at the height of American dynamism,.

Any society’s approach to building sums up the whole: its purpose, sense of its own place in history, what the future could be and . Buildings are monuments to the future and even to our future selves, why not transform a skyline now to inspire yourself to strive for greatness a decade from now? Today’s planning regulations are a microcosm of the obstacles that stymie progress, perhaps if the financial burden of applications, appeals and time delays caused by objections was reduced, or even removed, public buildings could challenge all that is physically possible in the way Boullée imagined.

Bibliothèque du Roi - interior

Source: The Morgan Library

Schwarzman Library Reading Room

Source: Marymount Manhattan

Hope

‘It is to you who cultivate the arts that I dedicate the fruits of my long vigils; to you who, with all your learning, are persuaded – and doubtless rightly so – that we must not presume that all we have left is to imitate the ancients!’ – Etienne-Louis Boullée, Essai sur l'Art (1796)

Little of Boullée’s work stands except for the Hôtel Alexandre and the chapel at Église Saint Roche. Though their sizes pale in comparison to his grandest visions, both demonstrate the power of combining scale, detail and material in a way that achieves more than many modern buildings. Unconstrained by planning proposals or endless bureaucracy, the Hôtel Alexandre’s draft drawings were fully realised and the building stands in its original form save for the mansard roof added later, a feature of neoclassical technique that would elevate the richness of almost all residential streets as demonstrated by a report by Samuel Hughes. As Boullée’s constructs faded away in revolutionary France, he was largely forgotten though his influence, particularly with regards to incorporating the neoclassical style, lived on through Jean Chalgrin and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand among others, until his name reappeared in the public’s eye through Greenaway’s ‘The Belly of an Architect’, a rambling film that depicts an American architect’s journey to Italy to stage an exhibition in honour of Boullée which gets derailed by his wife’s affair and then his eventual suicide.

Nonetheless, the film’s moderate success upon release ensured that Boullée’s identity started to redevelop its fullness which has maintained itself four decades later thanks to the Internet with communities like Vienna Canvas providing space for Boullée to speak for himself.. Immortalised through his drawings and what still stands of his work, his philosophy must be used as a foundation upon which society can achieve its architectural potential, every civilisation’s high point is marked by what it builds, and out of this building flows its ideas. Achieving progress is only attainable through pushing architecture to its limits in ways that respect scale, nature and material that creates substantive works that through their beauty inspire the public.

Hôtel Alexandre Facade

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Église Saint Roche Chapel

Source: Wikimedia Commons

No pursuit epitomises Boullée’s ideals more than More Monuments, established to build statues as a homage to builders, and to idealise progress, Mo Mahmood’s vision of structures that will ‘mesmerise generations to come’ encapsulates all that must become part of modern architecture again.Hope lies in finding and encouraging those willing to take the torch from Boullée and to instil all that is beautiful about nature at the centre of architecture again. Economic reasons precluded Boullée from achieving many of his visions, Monumental Labs founded by Micah Springut uses AI-enabled Computer Aided Manufacturing to drastically reduce the cost of building sculptures and monuments, at no point in human history have grand designs been more economically accessible. For this reason, capturing the essence of Boullée’s work is possible and is indeed of civilisational importance to enable modern architecture to fuel progress. Architecture has a purpose beyond the functional, architecture epitomises the culture of the time with what we build epitomising society’s ambition and inspiring its builders.

Sources

Essai sur l'Art (written 1796, published 1974) - Etienne-Louis Boullée

Ireland’s Planning and Development Act (2000)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Andrew Rose for initially suggesting that I reflect on my thoughts on building and write about them. Jamie Croucher*, Amaan Ahmad, Jacopo Gabrielli Matthew Chiu, Fergus McCullough and Spencer Burleigh provided their thoughts on an early draft of this essay. My interest in progress, as an idea and pursuit, is due to Tyler Cowen, Patrick Collison, Arnaud Schenk and Jason Crawford. A conversation with Mo Mahmood of More Monuments was immensely helpful.

*Jamie currently has no social media presence. He works at the NATO Innovation Fund.